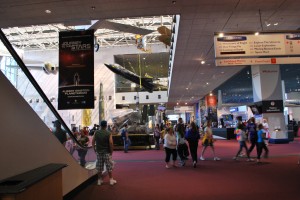

The National Air and Space Museum (NASM) is a part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.. It holds the largest collection of airplanes and spacecraft in the world.

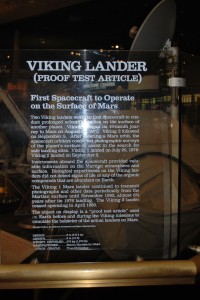

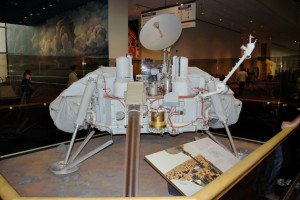

In 1976, the museum was established and became the center for research on the history and science of aviation and spaceflight. It also functions as a place for planetary science, terrestrial geology and geophysics. The space and aircraft on display are authentic or backups of the original equipment.

The museum is the second most popular in D.C. compared to the National Museum of Natural History. It has an annex site located at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles International Airport. Most restoration in the museum is conducted at the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland.

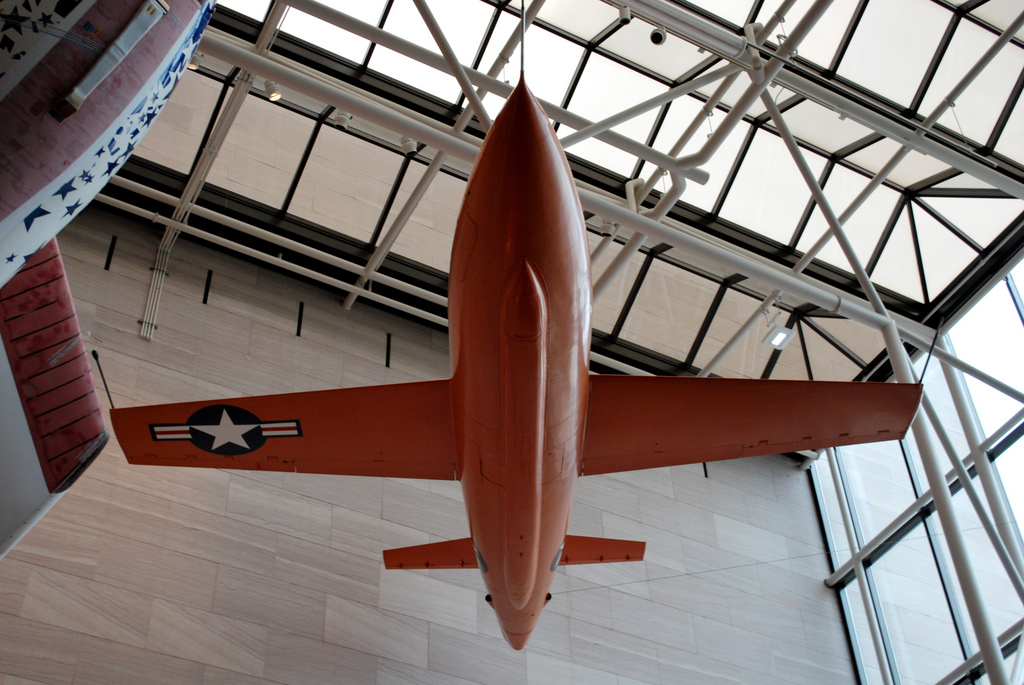

Due to the museum’s close proximity to the United States Capitol, the museum was designed not to stand out too boldly. Gyo Obata, a St. Louis-based architect from Hellmuth and Kassabaum accepted the challenge to design the museum as four simple marble-encased cubes containing the smaller and more theatrical exhibits. It is connected by three spacious steel-and-glass atria housing the larger exhibits such as missiles, airplanes and spacecraft. The west glass wall of the building is used for the installation of airplanes and functions as a giant door.

The museum was originally called the National Air Museum when President Harry Truman signed its formation into law. The collection in the museum dates back to the 1876 Centennial Exposition (Philadelphia) after which the Chinese Imperial Commission donated a group of kites to the Smithsonian. The Stringfellow steam engine was included into the collection in 1889, the first piece actively acquired by the Smithsonian.

There was no single building that could hold all the items obtained from the Army, Navy, domestic and captured aircraft from World War I, so the pieces that are not in the museum were on display in the Arts and Industries Building. The other artifacts are stored in the Aircraft Building known as the “Tin Shed”, (a large temporary metal shed) located in the south yard of the Smithsonian Castle. The rockets and larger missiles were displayed outdoors in what was known as Rocket Row. The shed housed the Martin bomber (a LePere fighter-bomber) and an Aeromarine 39B floatplane.

The large numbers of aircraft donated to the Smithsonian after World War II and the need for hangar and factory space for the Korean War drove the Smithsonian to look for its own facility to store and restore aircraft. The current Garber Facility was ceded to the Smithsonian by the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission in 1952. Bulldozers from Fort Belvoir and prefabricated buildings from the United States Navy kept the initial costs low for the much-needed space.

During the height of the space race in the 1950s and 1960s, the museum was renamed to the National Air and Space Museum. Congress passed the congressional appropriations for the construction of the new exhibition hall, which opened July 1, 1976 at the height of the US Bicentennial festivities under Director Michael Collins, who had flown to the Moon on Apollo 11.

The museum received several artifacts that include the former camera from the Hubble Space Telescope after Space Shuttle mission STS-125. The museum also holds the backup mirror for the Hubble. The plans to install Hubble in the museum and retrieve it from space failed to materialized after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003. The mission was considered too risky. The museum was also supposed to receive the International Cometary Explorer, which is currently in a solar orbit if NASA were to retrieve the satellite.

In March 1994, controversy erupted due to the proposed 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing in Japan. The exhibit center piece features the Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped the A-bomb in Hiroshima. Airforce veterans and Retired Officers from the armed forces argued strongly against the inclusion of Japanese accounts and photographs politicized the exhibit and insulted U.S. airmen. They also disputed that the U.S casualties that would have resulted from a Japanese invasion was reduced by 75%. The American Legion called for a congressional investigation and members of congress called for Martin O. Harwit’s resignation. Harwit was forced to resign from NASM. The National Air and Space Museum (NASM) placed the forward fuselage of the Enola Gay and other items as a part of historical exhibition. It was the most popular special exhibition in the history of the museum and draw nearly 4 million visitors before it closed in May 1998.